Federalism, as a political theory and system, advocates for the division of powers between a central authority and constituent political units, typically aiming for shared governance while maintaining autonomy. In the context of European regional integration, federalism has played a foundational and ideological role, offering a framework for understanding the evolving nature of the European Union (EU). However, it also faces limitations in fully capturing the complex dynamics and political realities of European integration.

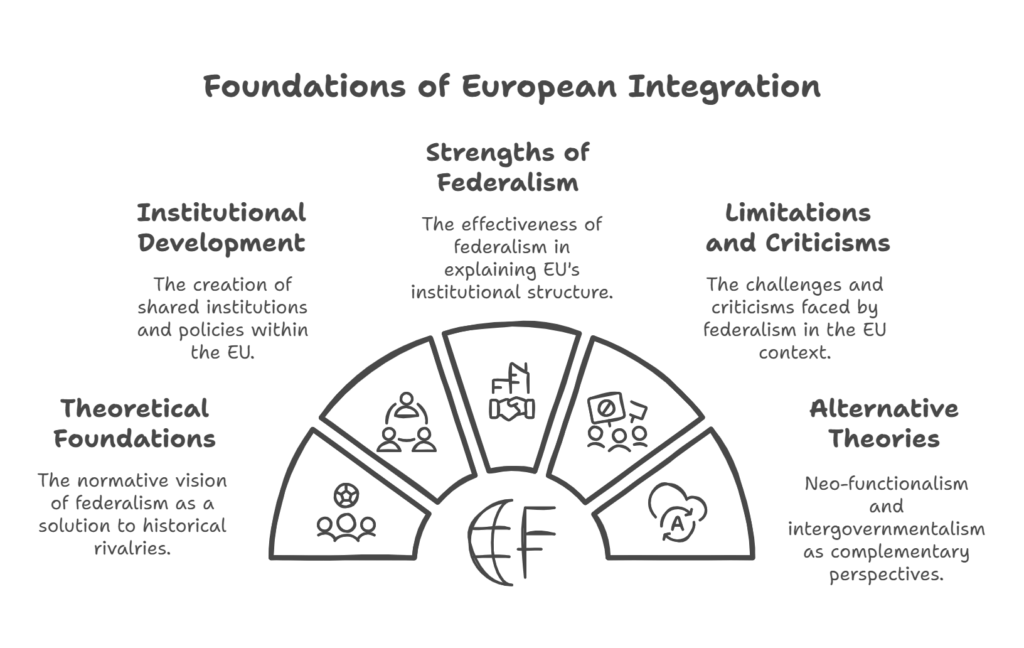

Theoretical Foundations of Federalism and European Integration

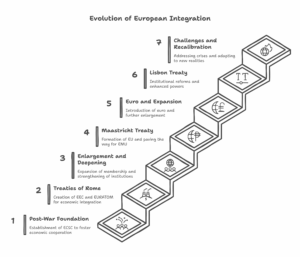

Federalism in Europe emerged as a normative vision following the devastation of World War II. Thinkers like Altiero Spinelli and Jean Monnet saw federalism as a solution to the historic rivalries that had plunged Europe into conflict. They believed that a supranational European federation would ensure peace, prosperity, and democratic stability. The 1951 European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community (EEC), were early steps toward creating a federal Europe, where member states would pool sovereignty in select domains.

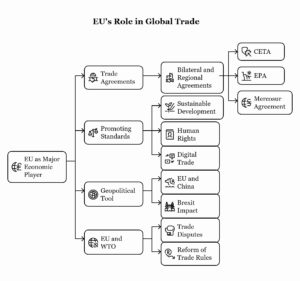

Federalism provides a useful lens through which to view integration processes like the creation of shared institutions (e.g., European Commission, European Parliament, and European Court of Justice), the adoption of common policies (e.g., competition and trade policy), and the gradual expansion of policy competencies from economic to political and social spheres. It helps explain the incremental deepening of institutional powers over the decades.

Strengths of the Federalism Model

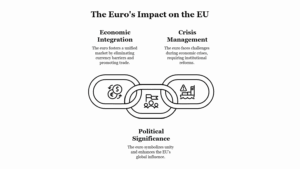

Federalism is particularly effective in explaining the EU’s institutional development. The EU exhibits features of a federal system: it has its own currency (Eurozone), legislative body (European Parliament), executive (European Commission), and judiciary (European Court of Justice). The supremacy of EU law over national laws in many areas resembles the hierarchical structure of federal systems.

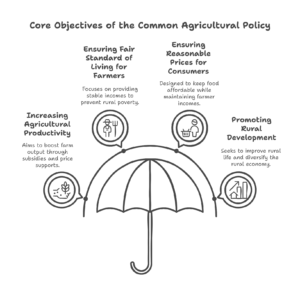

Moreover, federalism accounts for the normative aspirations of European integration, including the commitment to solidarity, subsidiarity, and rule of law. The EU has also developed shared citizenship rights, internal market freedoms, and common external representation in trade, all elements consistent with federal governance.

Limitations and Criticisms

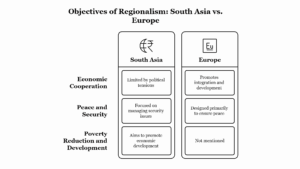

Despite its explanatory power, federalism is limited as a theory of European integration. The EU is not a federation in the traditional sense but a hybrid entity—often termed a “sui generis” polity. Member states retain significant sovereignty, especially in areas like foreign policy, taxation, and defense. Decisions often require unanimity or consensus, reflecting intergovernmental, rather than federal, dynamics.

Moreover, public resistance to deeper integration, as seen in the failure of the European Constitution (2005) and the rise of Euroscepticism, suggests that the federal vision is far from universally accepted. The “democratic deficit” criticism also highlights that EU institutions lack the kind of popular legitimacy found in federal nation-states.

Neo-functionalism and intergovernmentalism have emerged as alternative or complementary theories. Neo-functionalism explains integration as a spillover effect from economic to political sectors, while intergovernmentalism focuses on the role of national governments as the primary drivers of integration. These perspectives emphasize pragmatism and national interest rather than normative commitments to federalism.

Conclusion

Federalism offers a compelling theoretical lens for understanding the architecture and aspirations of the European Union. It captures the long-term vision of a united Europe with shared governance and pooled sovereignty. However, it is not sufficient on its own to explain the multi-speed, multi-level nature of European integration. The EU is better understood as a dynamic political system combining federal and intergovernmental elements, shaped by political bargaining, legal developments, and shifting public sentiments. Thus, while federalism remains a valuable part of the theoretical toolbox, it must be complemented by other approaches to fully grasp the complex and evolving nature of European integration.

Leave a Reply